As of right now, it does not appear that European debt markets are buying into the program here. For instance, we have not seen Italian bond yields gap down:

The same troubling thing holds true in Portugal:

The issue, as I see it, is a similar one to what we went through in 2009. Let's back up for a moment here and state clearly why sovereign debt defaults are important to us: they threaten the health of major banks. That's the whole reason that even more stable countries live in mortal fear of a Greece or a Portugal going under. Banks like buying sovereign debt for their reserves due to its low default rate. If the debt they buy becomes distressed so they have to mark it down or if the borrowers default, that undermines the banks' capitalization and they need to, at best, issue more shares to recapitalize, which dilutes the value of existing shareholders. In a worst case scenario, the whole rotten thing comes crashing down and the banks fail catastrophically. I think that we all know the consequences that stem from that scenario.

As such, just like the situation we faced in early 2009, this is about whether the banks can reasonably attain enough capital to recapitalize to offset massive losses coming down the pike. In our case, it was the continuing doubts over the mountains of bad mortgages that banks were carrying on their books above the likely value that they could realize those assets at. Investors speculated for weeks and months about just what kind of hits our banks would have to take and it caused our markets to go into a total tailspin that took the Dow down to 6,500 at one point. Just an aside, there is no rational model by which one can call that a fair price for the market at that point. What came along to really solve the issue were the stress tests of our banks that detailed the amounts our banks needed to raise in additional capital in order to survive two differing economic scenarios. While there was criticism over the rigor of the tests at the time, it really did prove to be a turning point, along with expansionary monetary and fiscal policy that had begun just before that. They put a number on how much the banks would have to raise and investors could use that figure to pivot their decision making on whether or not to buy shares. Before that point, it had been somewhat of an unknown.

The markets had already begun a recovery before the release of the test results in May 2009 (the bottom was March 9th), including a massive rally in bank shares, but as the year went on, the financial stocks eventually added another huge leg to their rally in the summer as the recapitalizations went along without much incident. From then on in, the markets regained confidence, and things began to return to some level of normalcy. There were many other measures taken, so I don't want to exaggerate the importance of the stress tests, but the point is that once the health of the banks was assured, the markets and the economy at large could move on.

The key to Europe is whether the banks will now be sufficiently recapitalized. The stress tests there have been of questionable credibility, often only focusing on macroeconomic conditions and not pricing in what would happen with large write-downs of sovereign debt. That has started to change in the most recent iterations, but some analysts think that the stress tests are low-balling the needed capital by as much as $200 billion. As long as investors are not convinced that the banks' balance sheets are now as secure as the Maginot Line... wait a moment... as unsinkable as the Titanic... as solid as the walls of Constantinople... erm, well, pretty safe, we will be prone to a renewed crisis.

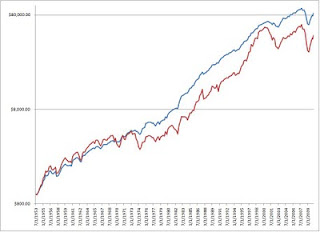

Of course, history may well show that this was the turning point and many of the naysayers have been wrong. After all, credit spreads here did not really start coming in until a full month after the stock market bottomed in March of 2009. (CLICK ON IMAGE FOR LARGER PICTURE)

Spreads did not begin their true downward trajectory until early to mid April and did not actually reach quasi-normal levels until October. In other words, it could be a while before we really know. At this moment, I am doubtful that we have seen the last of this crisis.