With that out of the way, JCP rallied quite a bit today, jumping 16.25% to $9.73, its highest close since about November, on a favorable earnings report last night. Sales growth topped estimates and the losses were narrower. See this press release for the overview: http://www.marketwatch.com/story/jcpenney-reports-fiscal-2014-first-quarter-results-2014-05-15

Part of the reason same store sales growth was pretty solid at 6.2% was due to a pretty favorable comparison since in the first quarter of last year they were really in their down stroke phase and sales dropped by solid double digits. Add to that the fact that closing your weakest performing stores prunes the numbers to give some extra lift and you get a pretty decent number. I'll be awfully curious to see if this can be maintained going forward.

Importantly, gross margins have started firming up and the company apparently expects them to continue to grow. It also appears that they are beginning to move toward eliminating their longstanding hemorrhage of cash. This is important since one of the very legitimate concerns with JCP is that the company was swiftly moving toward Chapter 11. Those concerns are gone for now. Based on present information, it's not easy to see how that risk is still relevant.

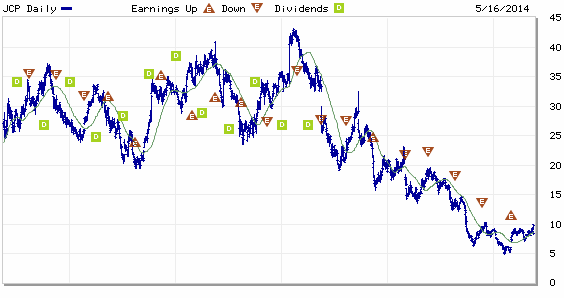

I think that their result today shores up my conviction in my January 2015 $10 calls, but I'm not exactly hot and bothered to add to the position. There are still a great many difficulties there, including the possibility of share price dilution should the company need to recapitalize. It doesn't have the prettiest balance sheet in the world with a shareholder's equity position that has fallen from $5.46 billion in 2011 to just over $3 billion now. This is also just a much smaller company than it once was, with revenues dropping from $17.76 billion in 2011 to $11.86 billion in 2014. While they seem to have stabilized at the present level, it's quite unlikely that they'll be making any runs at their old all-time highs anytime soon. Just to give a sense of what has happened to it, have a look at this:

|

| Chart courtesy of Marketwatch.com |

Here are some stories by those that have spent more time than me on JCP, first those expressing caution:

The Value Investor at Seeking Alpha: http://seekingalpha.com/article/2223443-j-c-penney-a-battle-has-been-won-but-not-the-war

Morgan Stanley: http://www.benzinga.com/analyst-ratings/analyst-color/14/05/4562916/update-morgan-stanley-reiterates-on-j-c-penney-company-o

Michael Maggi at The Street: http://www.thestreet.com/story/12712120/1/jc-penney-stock-delaying-the-inevitable-disappearing-coin.html?puc=TSMKTWATCH&cm_ven=TSMKTWATCH

On the more bullish side, we have these stories:

Achilles Research at Seeking Alpha: http://seekingalpha.com/article/2222573-j-c-penney-you-aint-seen-nothing-yet-well-on-its-way-to-18

Dante's Investing Ideas at Seeking Alpha: http://seekingalpha.com/article/2222473-giddy-up-j-c-penney-could-hit-22-sometime-this-year

Of course, this is what makes a market. I'm a little cautious myself since the department store industry in general isn't a particularly great one at the moment, even if JCPenney is embracing an online presence very aggressively. Its glory days are, I think, in the past and we're just basically speculating that it got undervalued due to death-spiral concerns about its liquidity. If it can hang on and restore modest profitability, JCP makes sense for my position and for maybe some quick trades, but I'm skeptical regarding its long-term prospects.

Of course, I've been burned on clothing retailers before, so I'm prepared to be surprised again.